| |

|

The Loggia dei Lanzi , also called the Loggia della Signoria, is a building on a corner of the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, Italy, adjoining the Uffizi Gallery. It consists of wide arches open to the street. Starting from the 16th century, with the creation of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the definitive suppression of the republican institutions, the Loggia is effectively an open-air sculpture gallery of antique and Renaissance art.

Underneath the bay on the far left is the bronze statue of Perseus by Benvenuto Cellini. It shows the mythical Greek hero holding his sword in his right hand and holding up the Medusa's severed head in his left. On the far right is the manneristic group Rape of the Sabine Women by the Flemish artist Giambologna. This impressive work was made from one imperfect block of white marble, the largest block ever transported to Florence.

The sculpture Patroclus and Menelaus is another marble statue in the center of the Loggia dei Lanzi.

Menelaus Carrying the Body of Patroclus

The Pasquino Group (also known as Menelaus Carrying the Body of Patroclus or Ajax Carrying the Body of Achilles) is a group of marble sculptures that copy a Hellenistic bronze original, dating to ca. 200–150 BCE.[1] At least fifteen Roman marble copies of this sculpture are known.[1] Many of these marble copies have complex artistic and social histories that illustrate the degree to which improvisatory "restorations" were made to fragments of ancient Roman sculpture during the 16th and 17th centuries, in which contemporary Italian sculptors made original and often arbitrary and destructive additions in an effort to replace lost fragments of the ancient sculptures.[2]

One of the most famous versions of the composition, though so dismembered and battered that the relationship is scarcely recognizable at first glance,[3] is the so-called Pasquin, one of the talking statues of Rome. It was set up on a pedestal in 1501 and remains unrestored.[4] A version of the group, probably intended to represent other Homeric figures, is part of the Sperlonga sculptures found in 1957.

Menelao che sorregge il corpo morto di Patroclo,

Loggia dei Lanzi, Firenze

|

|

Roman art, Menelaus Carrying the Body of Patroclus, Loggia dei Lanzi, Piazza della Signoria, Firenze [b]

|

Subject

Ancient Roman copies of the original Greek sculptural group were first documented in Rome ca. 1500. During the 16th century, various authors proposed different identifications for the dead figure, including Hercules, Geryon, and Alexander the Great.[4] Bernhard Schweitzer's 1936 Das Original der sogennanten Pasquino-Gruppe identifies the subject of the group as Menelaus carrying the body of Patroclus; however, this identification has been questioned and the subject of Ajax carrying the body of Achilles is now widely accepted for most of the Roman copies.[5][6]

In the case of the very fragmentary group from Sperlonga, most scholars agree it is here intended to show Odysseus carrying the body of the dead Achilles off the battlefield outside Troy (or possibly Ajax doing the carrying), as the other sculptures in the ensemble show scenes from the story of Odysseus.[7] This is an unusual subject, not in Homer, but one that is mentioned by Ovid (Metamorposes, 13, 282 ff) and fits the rest of the programme.[8] Here Odysseus is shown at his most conventionally virtuous, demonstrating pietas.

The Loggia dei Lanzi group

Cosimo I, Grand Duke of Tuscany purchased an ancient marble fragment depicting the headless torso of a man in armor supporting a heroically nude dying comrade soon after it was discovered in the vigna of Antonio Velli, half a Roman mile beyond Porta Portese, Rome.[9] With the consent of Pope Pius V, it was taken immediately to Florence, where it appears in the inventory taken at Cosimo's death in 1574.[10]

|

| The project for completing the truncated torso of the "Ajax" figure, missing above the waist when it was found according to the Memorie (1594) of the sculptor and antiquarian Flaminio Vacca, was commissioned by Ferdinando II; the "restoration" was worked out by Pietro Tacca and executed by Lodovico Salvetti[11] from Tacca's model, according to Filippo Baldinucci.[12] The restoration based on a similar sculpture found in Palazzo Pitti and a Head of Menelaus, preserved in the Vatican Museums, dating back to the 4th century BC. It was set up in a niche on the south end of the Ponte Vecchio. Paolo Alessandro Maffei's engraving of 1704[13] shows that the "Ajax" figure then was wearing a helmet much simpler than the elaborate neoclassical one erroneously provided by Ricci seen on the sculpture today. |

|

|

| |

|

Giacomo Brogi (1822-1881), Menelao, busto in marmo, Roma (Vaticano)

|

In 1771, the neoclassic artist Anton Raphael Mengs took moulds of the parts he considered genuinely ancient (and thus original) of this sculpture and the version at the Palazzo Pitti (discussed below) and reassembled them in a plaster model that was intended to be more faithful to the Roman original.[14] It was taken away to be further repaired in 1798[15] and remained in obscurity, undergoing further adjustments by Stefano Ricci in the 1830s, until it was finally re-erected in 1838, in the Loggia dei Lanzi in the Piazza della Signoria, Florence.[16] The feature which still draws most attention is the lifeless hanging left arm of the "Achilles" figure, seemingly dislocated, which was in fact part of the Tacca-Salvetti restoration.[17] Other errors in restoration are the lifted left leg of the bearer, the raised right knee of Patroclus, and the mounded ground that serves as a base.[18]

|

|

Arte romana, Menelao che sorregge il corpo morto di Patroclo (particolare)

Loggia dei Lanzi, Piazza della Signoria, Firenze [b]

|

Loggia dei Lanzi

|

|

|

|

|

|

Il Ratto delle Sabine, Giambologna, 1583 |

|

Benvenuto Cellini, Perseo con la testa di Medusa

|

|

Ercole e il centauro Nesso (Giambologna) |

|

|

|

|

|

Patroclo e Menelao , 1599,

Loggia dei Lanzi, Piazza della Signoria, Firenze

|

|

Pio Fedi, Neottolemo rapisce Polissena da Ecuba, 1855 - 1865, Piazza della Signoria, Loggia dei Lanzi |

|

Mercurio. Calco moderno della statuetta di Benvenuto Cellini in una nicchia della base del Perseo, nella Loggia dei Lanzi di Firenze. L'originale è esposto al Museo del Bargello a Firenze. Foto di Giovanni Dall'Orto.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Statua di una prigioniera barbara detta Thusnelda”. Marmo, opera romana di età traianeo-adrianea (II sec. d.C.) con restauri moderni. Scoperta a Roma; già nel 1541 nella collezione Capranica della Valle; dal 1584 a Villa Medici a Rome; a Firenze dal 1787, sotto la Loggia dei Lanzi dal 1789. |

|

Arte romana, donna togata detta una sabina con testa ritratto di matilda, 110 dc ca., con restauri moderni |

|

Arte romana, donna togata detta una sabina, 110 dc ca., con restauri moderni |

The second Medici group

The second version was a gift in 1570 from the Florentine Paolo Antonio Soderini of Rome.[19] It was said to have been found at the Mausoleum of Augustus.[20] Identified as Ajax, it stands in the Cortile del Ajaco of Palazzo Pitti.

Further fragments of other Roman copies of this group have appeared during the 20th century,[21] but more severe and careful modern criteria for restoration have led historians to avoid trying to restore them as a completed figural group, as past individuals attempted to do with the Pasquino group.

The Hadrian group

Five fragments of a Pasquino group were excavated from Hadrian's Villa by Gavin Hamilton in 1769.[22] This sculpture was a part of the Roman emperor Hadrian's collection of copies of Greek masterpieces. Unlike other copies, the deceased figure in Hadrian's copy is wounded on the back. This has been interpreted as evidence that Hadrian's copy was meant to represent Menelaus and Patroclus, since the Iliad states that he was killed by a blow to the back.[4] These fragments are in the Vatican Museums. The head of Menelaus is on display in the museum's Hall of Busts.[23]

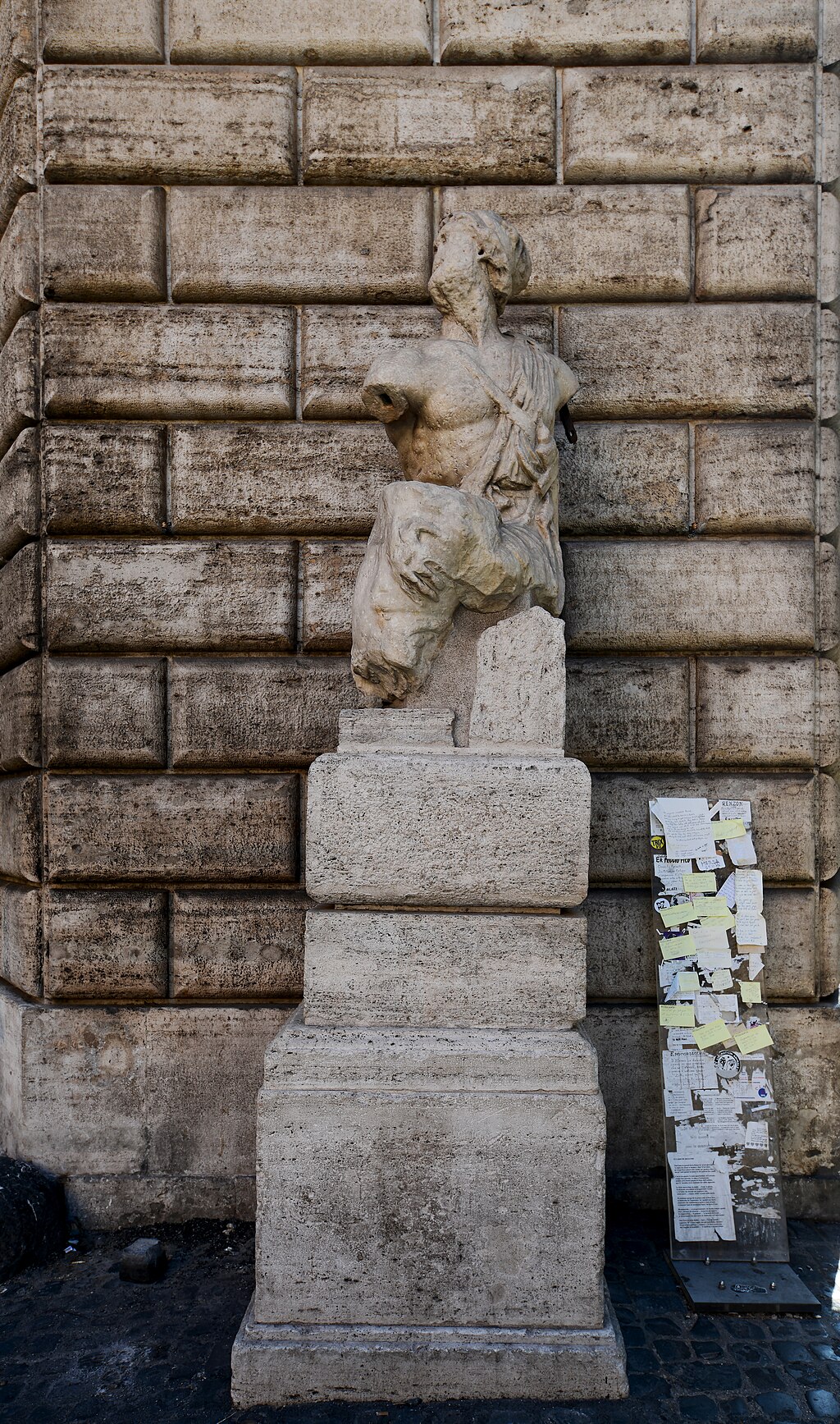

Pasquino |

Pasquino or Pasquin (Latin: Pasquillus) is the name used by Romans since the early modern period to describe a battered Hellenistic-style statue perhaps dating to the third century BC, which was unearthed in the Parione district of Rome in the fifteenth century. It is located in Piazza Pasquino on the southwest corner of the Palazzo Braschi (Museo di Roma), near the site where it was unearthed.

The actual subject of the sculpture is Menelaus supporting the body of Patroclus, and the subject, or the composition applied to other figures as in the Sperlonga sculptures, occurs a number of times in classical sculpture, where it is now known as a Pasquino group.

The statue is known as the first of the talking statues of Rome, because of the tradition of attaching anonymous criticisms to its base. The satirical literary form pasquinade (or "pasquil") takes its name from this tradition.[24]

Pasquino gave his name to the word for a mocking, clandestine lampoon, the "pasquil" or "pasquinade," which entered several European languages in the sixteenth century. His was a genre nicely timed for the triumph of absolute monarchy. In Rome the term "pasquinata" soon took on a more general meaning as any written criticism of papal government, even if it was only circulated privately among acquaintances.[24]

Further reading:

Pasquino and the talking statues of Rome

The talking statues of Rome

|

|

La statua di Pasquino, III secolo a.C., Piazza Pasquino, Roma La statua di Pasquino, III secolo a.C., Piazza Pasquino, Roma

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Piazza della Signoria, Firenze, immagini dell'album

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Palazzo Vecchio, Loggia dei Lanzi, Piazza della Signoria, Firenze

|

|

Loggia dei Lanzi, Piazza della Signoria |

|

Ercole e il centauro Nesso (Baccio Bandinelli) e la Loggia dei Lanzi, Piazza della Signoria, Firenze

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Art in Tuscany | The Loggia della Signoria | The Loggia dei Lanzi

|

|

|

BibliograPHY

Andreae, Bernard, review of Sperlonga und Vergil by Roland Hampe, Gnomon, Vol. 45, Issue 1 (February 1973), pp. 84–88, Verlag C.H.Beck, JSTOR

Blanckenhagen, Peter H. von, review of Die Skulpturen von Sperlonga by Baldassare Conticello and Bernard Andreae, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 80, No. 1 (Winter, 1976), pp. 99–104, JSTOR

Herrmann, Ariel, review of Sperlonga und Vergil by Roland Hampe, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 56, No. 2, Medieval Issue (Jun. 1974), pp. 275–277, JSTOR

Weiss, H. Anne, "Odysseus at Sperlonga: Hellenistic Hero or Roman Foil?", in From Pergamon to Sperlonga: Sculpture and Context, Editors: Nancy Thomson De Grummond, Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway, 2000, University of California Press, ISBN 0520223276, 9780520223271, google books

Francesco Lumachi, Firenze, nuova guida illustrata, storica, artistica, anerdottica della città e dintorni Firenze, Società Editrice Fiorentina 1929

C. Paolini, La Loggia dei Lanzi. Una storia per immagini, Quaderno n. 15, Polistampa, Firenze, 2006.

Mary McCarthy, The Stones of Florence, Harcourt Brace International (1998), ISBN-10: 9780156850803 - ISBN-13: 978-0156850803

Mary McCarthy, De stenen van Florence, Het Spectrum, Schrijvers over de wereld, 1989, ISBN 9789027422071

McHam, Sarah Blake. "Donatello's Bronze David and Judith as Metaphors of Medici Rule in Florence." The Art Bulletin 83, no. 1 (March 2001): 32-47. Accessed September 20, 2013.

|

|

|

|

[a] Photo by i Marie-Lan Nguyen, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Genericlicense.

[b] Menelaus holding the body of Patroclus, Roman marble copy of the Flavian era, after a Greek statue (240-230 B.C.). Restored in 1640 by Ludovico Salvetti according to a model by Pietro Tacca and in 1830 by Stefano Ricci. Discovered in Rome, property of the Medici from 1570, first placed near Ponte Vecchio, then in the Loggia dei Lanzi in 1741.Foto di Sailko, icenziato in base ai termini della licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione 3.0 Unported.

[1] Stewart, Andrew (2017). Art in the Hellenistic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 118.

[2] The sculpture is one of three versions of the "Pasquino" discussed by Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500–1900 (Yale University Press) 1981: 291–96, cat. no 72. "Pasquino"; Giovanna Giusti Galardi, The Statues of the Loggia Della Signoria in Florence: Masterpieces Restored 2002:45–51.

[3] It was remarked upon as a matter of fact by Flaminio Vacca, Memorie... 1594, quoted in note 4, below; the identification as Menelaus with the dying Patroclus was made by Francesco Cancellieri, Notizie delle due famose statue di un fiume et di Patroclo dette volgarmente di Marforio et di Pasquino (Rome 1789), noted in Haskell and Penny 1981:291 note 2.

[4] Epic Visions: Visuality in Greek and Latin Epic and Its Reception. Lovatt, Helen, 1974–, Vout, Caroline. Cambridge. 2013. p. 203

[5] Schweitzer, Bernhard (1936). Das Original der sogennanten Pasquino-Gruppe. S. Hirzel. pp. 53–60.

[6] Stewart, Andrew (2017). Art in the Hellenistic world: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 119.

[7] Following Andreae, with Hampe and Herrmann unconvinced, Herrmann, 276. See also Blanckenhagen, 102; Weiss, 117–124 identifies the pair as Aeneas and Lausus.

[8] Blanckenhagen, 102

[9] "97. Mi ricordo che fuori della detta porta Portese mezzo miglio, dov'è la vigna di Antonio Velli, vi fu trovato un Pasquino sopra un piedistallo di tufa, con un Gladiatore, che gli muore in braccio; il detto Pasquino era mancante fino alla cintura, ma il Gladiatore sano : e quando venne il Duca Cosmo ad incoronarsi in Roma Gran Duca, lo comprò, per scudi cinquecento, e lo condusse a Fiorenza accompagnatolo con l'altro, che ebbe da Paolo Soderino, trovato nel Mausoleo di Augusto." Flaminio Vacca, Memorie... 1594; see also Rodolfo Amedeo Lanciani, The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome: A Companion Book for Students 1897:547, noting Francesco Cancellieri, Notizie sulle statue di... Pasquino (Rome, 1779).

[10] Haskell and Penny 1981:294-95 note 23.

[11] Lodovico Salvetti, like Tacca a former garzone in the studio of Giambologna, was a minor Florentine sculptor who worked as Tacca's assistant.

[12] Baldinucci, Notizie dei professori del disegno... ii:168.

[13] Included in Maffei's Raccolta di statue antiche e moderne, plate xlii (Rome, 1704).

[14] Galardi 2002.

[15] After the Treaty of Tolentino (February 1797) Napoleonic agents were assessing all the public and noble collections of Italy to see which antiquities should be removed to Paris. Many of the antiquities of Naples were removed by ship to safety in Sicily by the Neapolitan Bourbons in exile.

[16] Haskell and Penny 1981:295-95; earlier discussions of placing it in the Loggia dei Lanzi had never been acted upon.

[17] "In fatti nel gruppo del Ponte Vecchio il torso della prima figura, ed il braccio sinistro della seconda è moderno." (Saggio istorico della Real galleria di Firenze(1779) vol. ii note xxxv to p. 20.

[18] Pointed out by Erna Mandowsky, "Two Menelaus and Patroclus Replicas in Florence and Joshua Reynolds" The Art Bulletin 28.2 (June 1946:115–118) p. 115.

[19] According to Flaminio Vacca, Memorie di varie antichità trovate in diversi luoghi della Città di Roma, 1594 (Haskell and Penny 1981:295).

[20] For Soderini's archaeological activities at the Mausoleum of Augustus, see Anna Maria Riccomini, "A Garden of Statues and Marbles: The Soderini Collection in the Mausoleum of Augustus" Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 58 (1995, pp. 265–284) p. 281f.

[21] Bernhard Schweitzer listed all the fragments known as of 1936, in "Das Original des sogennanten Pasquino-Gruppe", on Abhandlungen der philologisch-historischen Klasse der sächsischen Akademie der Wissenshaften 43.4 (Leipzig) 1936:1ff; he reported the particular parts of the two Medici groups that are restorations.

[22] "Digital Hadrian's Villa Project". vwhl.soic.indiana.edu. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

[23] "Head of Menelaos | Museum of Classical Archaeology Databases". museum.classics.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

[24] Nussdorfer, Laurie (23 April 2019). Civic Politics in the Rome of Urban VIII. Princeton University Press. pp. 8–10.

|

° This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia articles Pasquino Group

and Pasquino, published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

|

|