| |

|

The Loggia dei Lanzi, a building on a corner of the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, adjoining the Uffizi Gallery, is effectively an open-air sculpture gallery of antique and Renaissance art.

Underneath the bay on the far left is the bronze statue of Perseus by Benvenuto Cellini. It shows the mythical Greek hero holding his sword in his right hand and holding up the Medusa's severed head in his left. On the far right is the manneristic group Rape of the Sabine Women by the Flemish artist Giambologna. The sculpture Patroclus and Menelaus is another marble statue in the center of the Loggia dei Lanzi.

Menelaus Carrying the Body of Patroclus

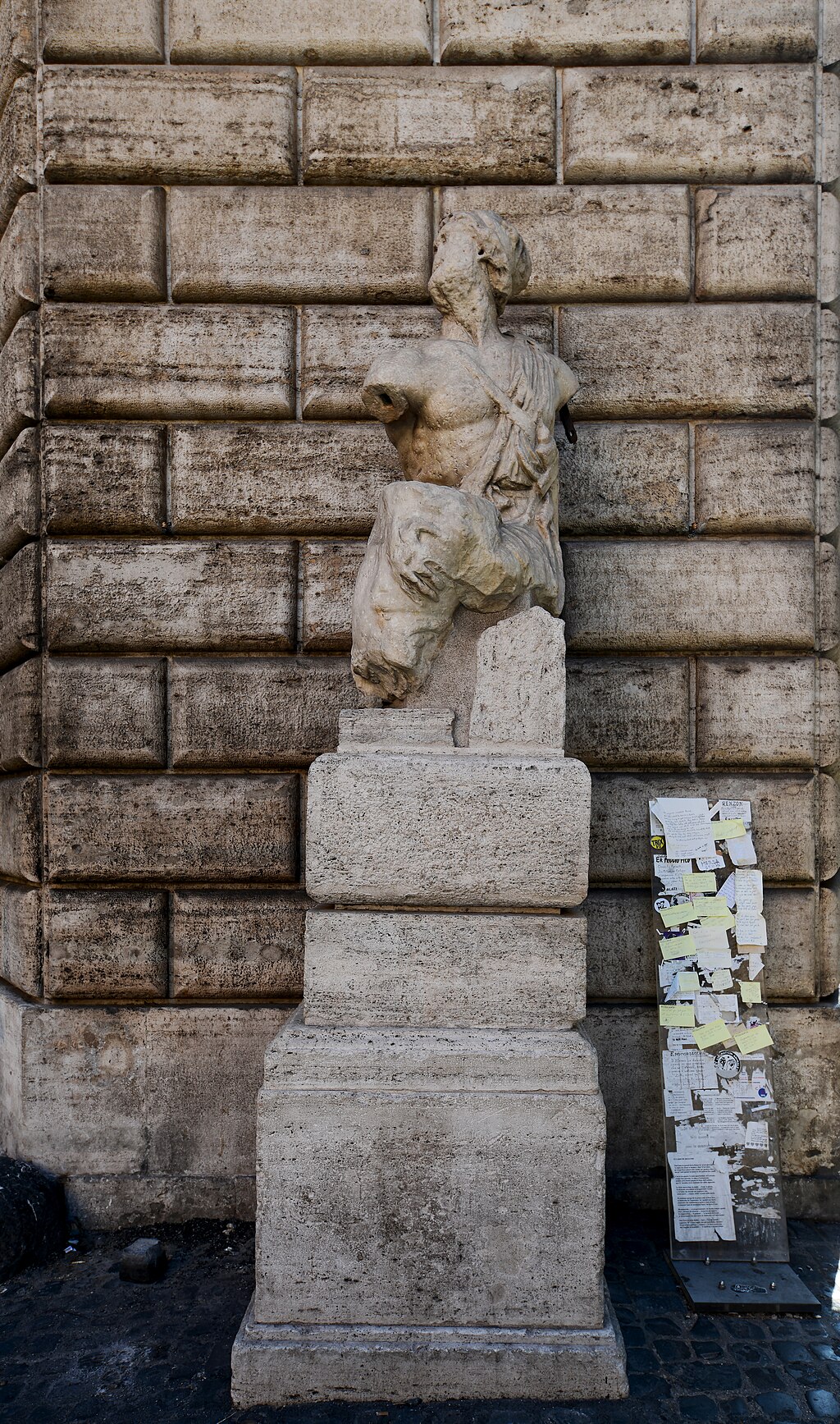

The Pasquino Group (also known as Menelaus Carrying the Body of Patroclus or Ajax Carrying the Body of Achilles) is a group of marble sculptures that copy a Hellenistic bronze original, dating to ca. 200–150 BCE.[2] At least fifteen Roman marble copies of this sculpture are known.[2] One of the most famous versions of the composition, though so dismembered and battered that the relationship is scarcely recognizable at first glance,[4] is the so-called Pasquin, one of the talking statues of Rome. It was set up on a pedestal in 1501 and remains unrestored.[5] A version of the group, probably intended to represent other Homeric figures, is part of the Sperlonga sculptures found in 1957.

Pasquino or Pasquin (Latin: Pasquillus) was unearthed in the Parione district of Rome in the fifteenth century. It is located in a piazza of the same name on the southwest corner of the Palazzo Braschi (Museo di Roma); near the site where it was unearthed.

The statue is known as the first of the talking statues of Rome, because of the tradition of attaching anonymous criticisms to its base. The satirical literary form pasquinade (or pasquil) takes its name from this tradition.[6]

The actual subject of the sculpture is Menelaus supporting the body of Patroclus, and the subject, or the composition applied to other figures as in the Sperlonga sculptures, occurs a number of times in classical sculpture, where it is now known as a "Pasquino group". The actual identification of the sculptural subject was made in the eighteenth century by the antiquarian Ennio Quirino Visconti, who identified it as the torso of Menelaus supporting the dying Patroclus; the more famous of two Medici versions of this is in the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence, Italy. The Pasquino is more recently characterized as a Hellenistic sculpture of the third century BC, or a Roman copy.[7]

The so-called Pasquin, one of the talking statues of Rome

|

|

The statue Pasquino, the first talking statue of Rome [8]

|

History |

| The statue's fame dates to the early sixteenth century, when Cardinal Oliviero Carafa draped the marble torso of the statue in a toga and decorated it with Latin epigrams on the occasion of Saint Mark's Day.

The Cardinal's actions led to a custom of criticizing the pope or his government by the writing of satirical poems in broad Roman dialect—called "pasquinades" from the Italian "pasquinate"—and attaching them to the statue "Pasquino".

Thus Pasquino became the first "talking statue" of Rome. He spoke out about the people's dissatisfaction, denounced injustice, and assaulted misgovernment by members of the Church. From this tradition are derived the English-language terms pasquinade and pasquil, which refer to an anonymous lampoon in verse or prose.[9]

Etymological origins

|

|

La statua di Pasquino, III secolo a.C., Piazza Pasquino, Rome. Postering on the statue is prohibited. "Pasquinades" must be placed on a side board. La statua di Pasquino, III secolo a.C., Piazza Pasquino, Rome. Postering on the statue is prohibited. "Pasquinades" must be placed on a side board.

|

| The origin of the name, Pasquino, remains obscure. By the mid-sixteenth century it was reported that the name "Pasquino" derived from a nearby tailor who was renowned for his wit and intellect;[10] speculation had it that his legacy was carried on through the statue, in "the honor and everlasting remembrance of the poor tailor".[10]

Tradition of wit

Before long, other statues appeared on the scene, forming a kind of public salon or academy, the "Congress of the Wits" (Congresso degli Arguti), with Pasquino always the leader, and the sculptures that Romans called Marphurius, Abbot Luigi, Il Facchino, Madama Lucrezia, and Il Babbuino as his outspoken colleagues.[11] The cartelli (translated as posters, placards, boards; probably the equivalent of pamphlet) on which the epigrams were written were quickly passed around, and copies were made, too numerous to suppress.[12] These poems were collected and published annually by the Roman printer Giacomo Mazzocchi as early as 1509, as Carmina apposita Pasquino, and became well known all over Europe.

The lampooning tradition was ancient among Romans.

Further reading:

The talking statues of Rome

|

|

.

Criticisms in the form of poems or witticisms were posted on the statue. It began in the 16th century and continues to the present day. Criticisms in the form of poems or witticisms were posted on the statue. It began in the 16th century and continues to the present day. |

|

The base of the statue Pasquino, the first talking statue of Rome [b]

|

Loggia dei Lanzi

|

|

|

|

|

|

Il Ratto delle Sabine, Giambologna, 1583 |

|

Benvenuto Cellini, Perseo con la testa di Medusa

|

|

Ercole e il centauro Nesso (Giambologna) |

|

|

|

|

|

Il Gruppo di Pasquino, (Patroclo e Menelao), 1599, Loggia dei Lanzi, Piazza della Signoria, Firenze

|

|

Pio Fedi, Neottolemo rapisce Polissena da Ecuba, 1855 - 1865, Piazza della Signoria, Loggia dei Lanzi |

|

Mercurio. Calco moderno della statuetta di Benvenuto Cellini in una nicchia della base del Perseo, nella Loggia dei Lanzi di Firenze. L'originale è esposto al Museo del Bargello a Firenze. Foto di Giovanni Dall'Orto.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thusnelda (born c. 10 BC)

Germanic noblewoman captured by Germanicus, the grandson of Augustus and leader of an army that invaded Germania |

|

Salonia Matidia (68 AD - 119 AD)

daughter and only child of Ulpia Marciana and wealthy praetor Gaius Salonius Matidius Patruinus |

|

Agrippina Minor, (Cologne 15 AD - Misenum 59). Roman Empress and one of the more prominent women in the Julio-Claudian dynasty |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

The talking statues of Rome

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pasquino, the first talking statue of Rome |

|

Marforio, Roman, 1st century AD, marble - Musei Capitolini - Rome

|

|

Busto di madama Lucrezia

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abate Luigi, Piazza Vidoni

|

|

Campo Marzio - Fontana Babuino |

|

Roma, fontana del Facchino (con botticella), realizzata al tempo di Gregorio XIII, 1580

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Art in Tuscany | The Loggia della Signoria | The Loggia dei Lanzi

"The Statue of Pasquino" | www.museodiroma.comune.roma.it

|

|

|

BibliograPHY

Andreae, Bernard, review of Sperlonga und Vergil by Roland Hampe, Gnomon, Vol. 45, Issue 1 (February 1973), pp. 84–88, Verlag C.H.Beck, JSTOR

Blanckenhagen, Peter H. von, review of Die Skulpturen von Sperlonga by Baldassare Conticello and Bernard Andreae, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 80, No. 1 (Winter, 1976), pp. 99–104, JSTOR

Herrmann, Ariel, review of Sperlonga und Vergil by Roland Hampe, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 56, No. 2, Medieval Issue (Jun. 1974), pp. 275–277, JSTOR

Weiss, H. Anne, "Odysseus at Sperlonga: Hellenistic Hero or Roman Foil?", in From Pergamon to Sperlonga: Sculpture and Context, Editors: Nancy Thomson De Grummond, Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway, 2000, University of California Press, ISBN 0520223276, 9780520223271, google books

Francesco Lumachi, Firenze, nuova guida illustrata, storica, artistica, anerdottica della città e dintorni Firenze, Società Editrice Fiorentina 1929

C. Paolini, La Loggia dei Lanzi. Una storia per immagini, Quaderno n. 15, Polistampa, Firenze, 2006.

Mary McCarthy, The Stones of Florence, Harcourt Brace International (1998), ISBN-10: 9780156850803 - ISBN-13: 978-0156850803

Mary McCarthy, De stenen van Florence, Het Spectrum, Schrijvers over de wereld, 1989, ISBN 9789027422071

McHam, Sarah Blake. "Donatello's Bronze David and Judith as Metaphors of Medici Rule in Florence." The Art Bulletin 83, no. 1 (March 2001): 32-47. Accessed September 20, 2013.

|

|

|

|

[1] Photo by Yair-haklai, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Genericlicense.

[2] Stewart, Andrew (2017). Art in the Hellenistic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 118.

[3] The sculpture is one of three versions of the "Pasquino" discussed by Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500–1900 (Yale University Press) 1981: 291–96, cat. no 72. "Pasquino"; Giovanna Giusti Galardi, The Statues of the Loggia Della Signoria in Florence: Masterpieces Restored 2002:45–51.

[4] It was remarked upon as a matter of fact by Flaminio Vacca, Memorie... 1594, quoted in note 4, below; the identification as Menelaus with the dying Patroclus was made by Francesco Cancellieri, Notizie delle due famose statue di un fiume et di Patroclo dette volgarmente di Marforio et di Pasquino (Rome 1789), noted in Haskell and Penny 1981:291 note 2.

[5] Epic Visions: Visuality in Greek and Latin Epic and Its Reception. Lovatt, Helen, 1974–, Vout, Caroline. Cambridge. 2013. p. 203

[6] Nussdorfer, Laurie (23 April 2019). Civic Politics in the Rome of Urban VIII. Princeton University Press. pp. 8–10.

[7] Early discussion was summarised in B. Schweitzer and F. Hackenbeil, Das Original der sogennanten Pasquino-Gruppe (Leipzig: Hirtzl) 1936; the modern opinion is from Wolfgang Helbig.

[8] Photo by Peter Heeling, released into the public domain.

[9] Spaeth, John W. (1939). "Martial and the Pasquinade". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 70: 242–255.

[10] The Border Magazine". John Rennison. 22 March 1833 – via Google Books.

[11]

Ponti 1927; Enciclopedia Italiana, s.v. "Pasquino e Pasquinate".

[12] Copies in private daybooks have preserved some that were too scurrilous to print.

Surviving pasquinades from the sixteenth century have been published by Valerio Marucci, Anronio Marzo, and Angelo Romano, eds., PasqllinaJt romant del Ci"'lIiKetfJO, 2 vols. (Rome, 1983).[Nussdorfer, Laurie (23 April 2019). Civic Politics in the Rome of Urban VIII. Princeton University Press. p.10].

|

° This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia articles Pasquino Group

and Pasquino, published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

|

|